Heart Failure

Heart Failure is a clinical syndrome characterized by typical symptoms (e.g. breathlessness, ankle swelling and fatigue) that may be accompanied by signs (e.g. elevated jugular venous pressure, pulmonary crackles and peripheral oedema) caused by a structural and/or functional cardiac abnormality, resulting in a reduced cardiac output and/or elevated intracardiac pressures at rest or during stress.1

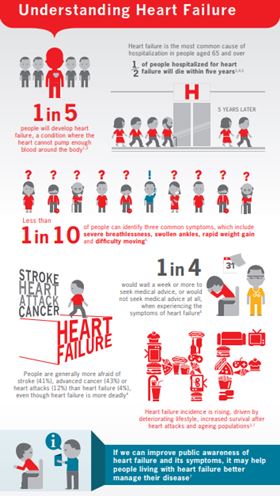

Understanding Heart Failure

The current definition of HF restricts itself to stages at which clinical symptoms are apparent. Before clinical symptoms become apparent, patients can present with asymptomatic structural or functional cardiac abnormalities [systolic or diastolic left ventricular (LV) dysfunction], which are precursors of HF. Recognition of these precursors is important because they are related to poor outcomes, and starting treatment at the precursor stage may reduce mortality in patients with asymptomatic systolic LV dysfunction.1,2

Understanding Heart Failure

Diagnosis

Demonstration of an underlying cardiac cause is central to the diagnosis of HF. (see chart) Identification of the underlying cardiac problem is crucial for therapeutic reasons, as the precise pathology determines the specific treatment used.1

|

Cause |

Examples |

|---|---|

|

Reduced ventricular contractility |

|

|

Ventricular outflow obstruction (pressure overload) |

|

|

Ventricular inflow obstruction |

|

|

Ventricular volume overload |

|

|

Arrythmia |

|

|

Impaired ventricular relaxation |

|

Classification

- According to ejection fraction

The main terminology used to describe Heart Failure is historical and based on measurement of the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). Differentiation of patients with Heart Failure based on LVEF is important due to different underlying aetiologies, demographics, co-morbidities and response to therapies.1 HF comprises a wide range of patients as you may see below:HF type

HFrEF

HFmrEF

HFpEF

1

Symptoms ± Signs

Symptoms ± Signs

Symptoms ± Signs

2

LVEF ≤ 40%

LVEF 41 – 49%

LVEF ≥ 50%

3

/

/

Objective evidence of cardiac structural and/or functional abnormalities consistent with the presence of LV diastolic dysfunction/raised LV filling pressures, including raised natriuretic peptides

The diagnosis of Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) is more challenging than the diagnosis of Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). Patients with HFpEF generally do not have a dilated left ventricular (LV), but instead often have an increase in LV wall thickness and/or increased left atrial (LA) size as a sign of increased filling pressures. Most have additional ‘evidence’ of impaired LV filling or suction capacity, also classified as diastolic dysfunction, which is generally accepted as the likely cause of HF in these patients (hence the term ‘diastolic HF’). However, most patients with HFrEF (previously referred to as ‘systolic HF’) also have diastolic dysfunction, and subtle abnormalities of systolic function have been shown in patients with HFpEF. Hence the preference for stating preserved or reduced LVEF over preserved or reduced ‘systolic function’.1

- According to NYHA classes

The NYHA functional classification has been used to describe the severity of symptoms and exercise intolerance. However, symptom severity correlates poorly with many measures of LV function; although there is a clear relationship between the severity of symptoms and survival, patients with mild symptoms may still have an increased risk of hospitalization and death.1,3,4

Recent European data (ESC-HF pilot study) demonstrate that 12-month all-cause mortality rates for hospitalized and stable/ambulatory HF patients were 17% and 7%, respectively, and the 12-month hospitalization rates were 44% and 32%, respectively. In patients with HF (both hospitalized and ambulatory), most deaths are due to cardiovascular causes, mainly sudden death and worsening HF. All-cause mortality is generally higher in HFrEF than HFpEF.1,5,6,7

- Ponikowski P, et al. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2129-2200.

- The SOLVD Investigators. N Engl J Med 1992;327:685–691.

- McMurray JJ. N EnglJ Med 2010;362:228–238.

- DunlaySM, et al. J Am CollCardiol2009;54:1695–1702.

- MosterdA, Hoes AW, Heart 2007;93: 1137–1146.

- Bleumink GS, et al. EurHeart J England; 2004;25:1614–1619.

- MaggioniAP, et al. EurJ Heart Fail 2013;15:808–817.